36

PERSONALquarterly 02/19

NEUE FORSCHUNG

_KARRIEREPLANUNG

covering three annual performance cycles of the firm. For more

details on the intervention timeline and a visualization of our

expectations, see Figure 2.

In our sample of 434 respondents who had filled out all the

surveys for the three waves, 29% were women, and 43% were

parents. The average age was 34.32 years (range 19-61 years),

and the actual hours worked were 44.3 hours per week. In our

final sample, in the first year, 47 employees customized down,

and 37 employees customized up, leaving 380 employees in

the common profile. In the second year, 64 employees custo

mized down, and 25 employees customized up, leaving 345 em

ployees in the common profile. The high number of employees

in the common profile is probably the combined result of our

strict definition (i.e., customizing on only one dimension does

not count), the organizational culture and the economic crisis,

in that employees feared to lose their job more than before.

To examine our research questions, we carried out different

statistical analyses. For example, to test whether MCC is benefi

cial for employees’ career outcomes in different life stages (e.g.,

mothers versus fathers, parents versus non-parents) we used

a General Linear Model – ANCOVA to compare means within

subgroups over time and across subgroups at one point in time.

In addition, we assessed the role of supervisors in shaping

intended implementation outcomes (e.g., lower employee turn

over intentions and higher engagement levels) with the use of

Latent Growth Modeling (Straub et al., 2018).

Involving supervisors turned out to be crucial

A very positive finding is that employees maintain high levels

of work engagement and low levels of turnover intentions over

time which confirms our assumptions that MCC reduces attri

tion and fosters employee engagement. However, as expected,

this was only the case if employee use of MCC was promoted

and supported by their supervisor.

Like earlier studies (Cooper/Baird, 2014, Nielsen/Randall,

2009), our findings show that a supervisor can influence inter

vention success, as employees indeed perceive an improvement

in support for combining career and care within their organi

zation in the MCC implementation. Improved perceptions of

support result in higher work engagement and lower turnover

intentions (see Table 1 for mediation results). Considering that

overall engagement levels declined, and turnover intentions

increased in our sample, supportive supervisors turned out to

be genuinely instrumental in achieving positive intervention

outcomes.

Not everyone benefitted from MCC

Different MCC choices (up or down) play out very differently

for employees, often depending on their gender and parental

status (see Table 2 for changes in means). Customizing up trig

gers an increase in career ambition, while there is a decrease

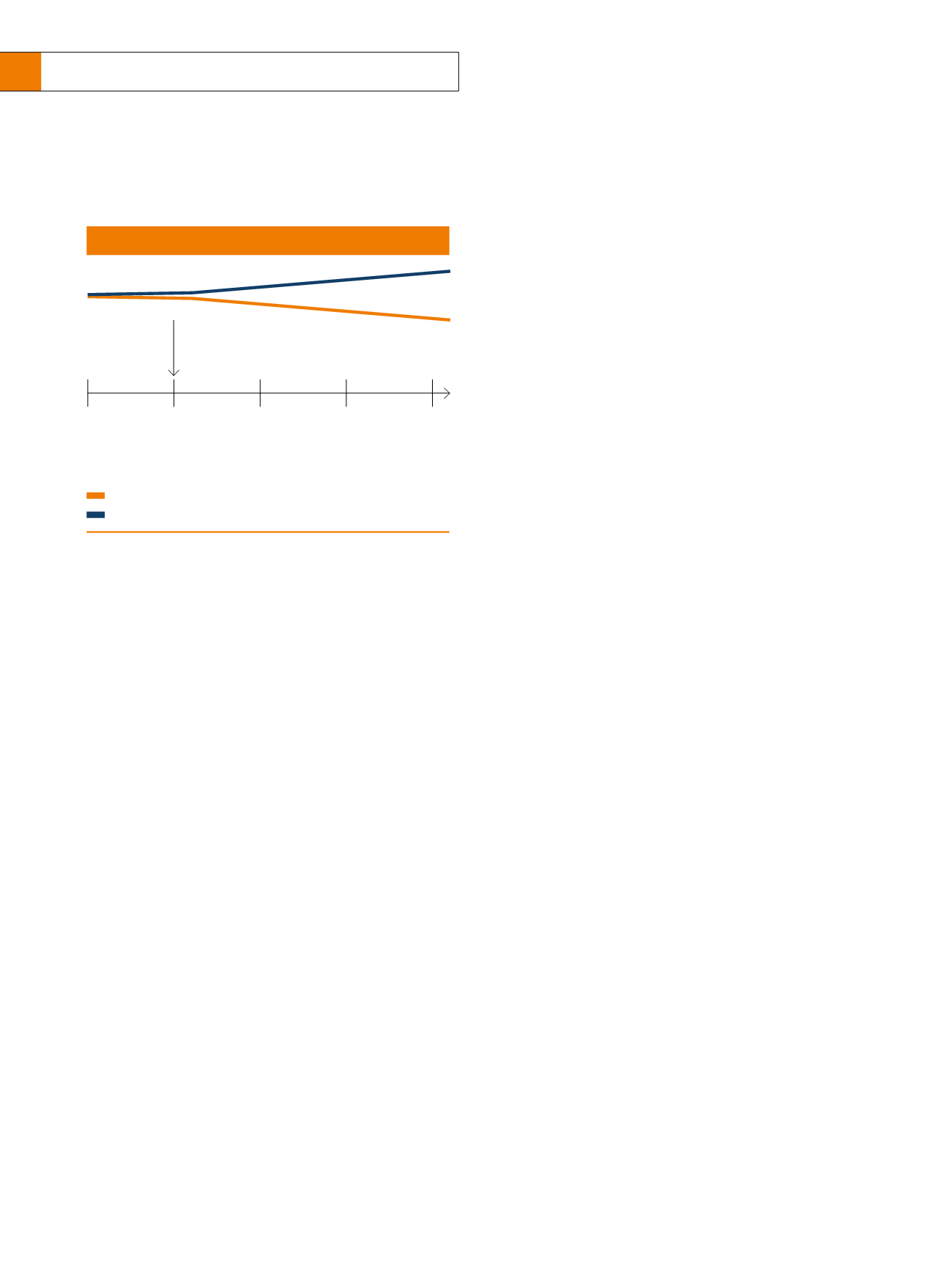

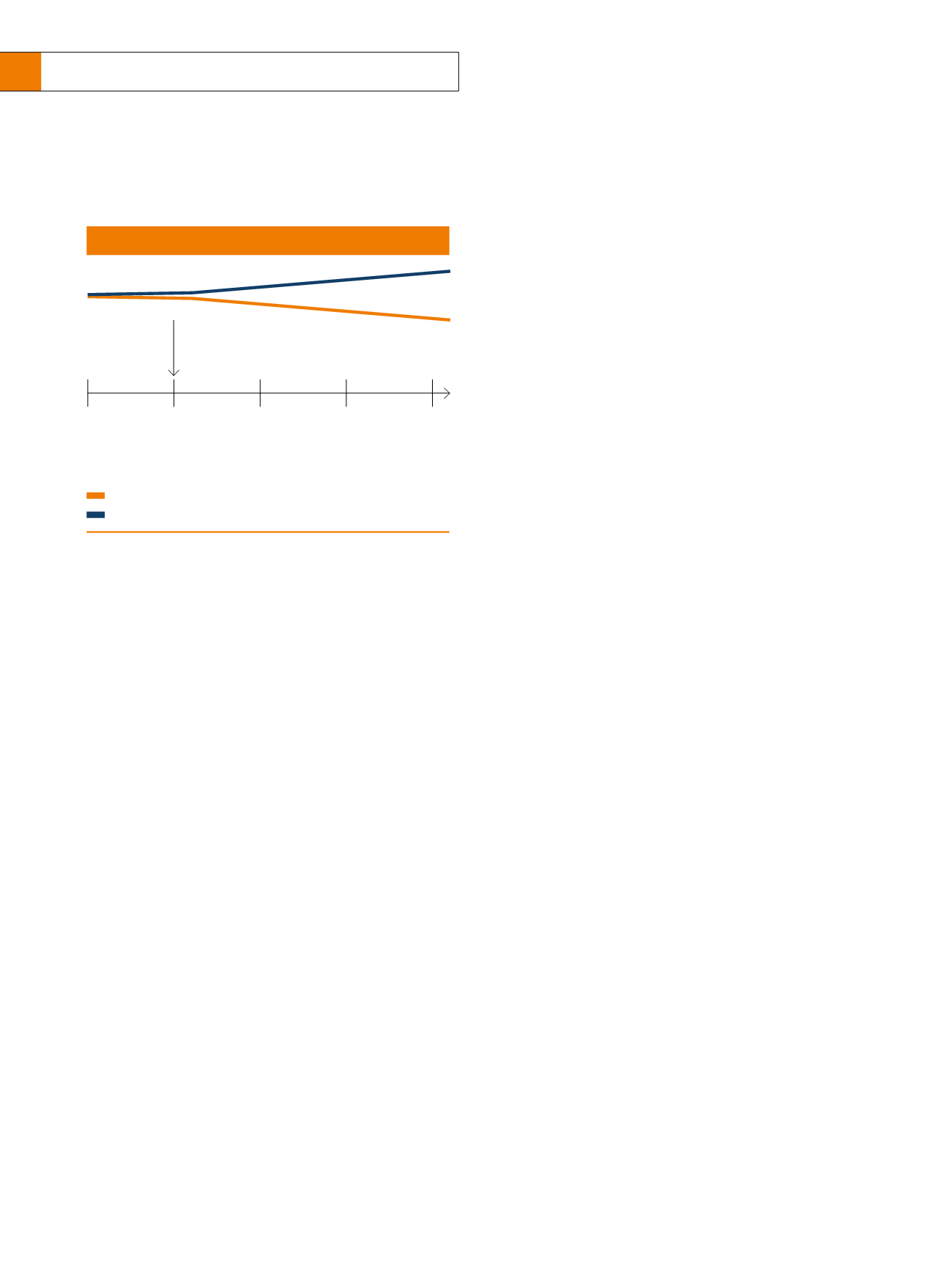

Figure 2:

Timeline of events and expected outcomes

Common profile – general downward trend (as observed prior to MCC)

Customized profile – general upward trend

June 2009

Time 1

1st Questionnaire

Pre-test

September

2009

MCC choice

selection together

with supervisor

MCC choice

selection together

with supervisor

Start of MCC

June 2010

Time 2

2nd Questionnaire

Pre-test

September

2010

June 2011

Time 3

3rd Questionnaire

Pre-test

As the organizational culture of many PSFs is often inherent

ly contradictory and ambiguous: they support and hinder em

ployees by expecting demanding work (e.g. long hours), and, at

the same time, provide flexibility (e.g. telework), we were also

interested in the role that supervisors played in the MCC im

plementation process, and their role of performance managers,

in shaping MCC outcomes. Thus, we assessed employee per

ceptions of supervisors’ support with MCC and their influence

on employee perceptions of organizational supportiveness.

Fitting with the research questions above, we expected that

customization would make employees feel better, thus have

positive effects on their work engagement, career satisfaction

and ambition, performance evaluations, and reduce turnover

intentions. We expected supervisors to influence perceptions

of the organizational culture positively.

How did we design our research?

Fitting with the growing demand from career researchers to

provide longitudinal data on individual careers, we developed

an online survey which was sent out to the entire workforce of

the firm in the Netherlands (n = 5605), shortly before MCC was

formally rolled out in 2009. The survey included items on de

mographic information, measures on employee perceptions of

organizational culture and supervisor support, and subjective

and objective career outcomes. We used well-established and

validated measures from the Organisational Behavior literature

(Cronbach Alphas for all measures were above .80). Over the

course of two years, we sent out two more waves, effectively

Quelle: Eigene Darstellung