6

SPEZIAL

|

CONTROLLING INTERNATIONAL

|

ISSUE 12

|

SEPTEMBER 2015

CONTROLLER

CA INTERNATIONAL

TRANSFER PRICES

AN IMPORTANT

INTERNATIONAL ISSUE

Dietmar Pascher,

Partner and Trainer of the

CA controller akademie,

Manager International

Program

Alternatively, in my most recent Stage II seminar I learned

about a case where a controller knew about activities

abroad, but not (yet) anything regarding the corresponding

tax consequences. Unfortunately, the tax department was

informed much too late about the activities, and this delay

resulted in high penalty payments.

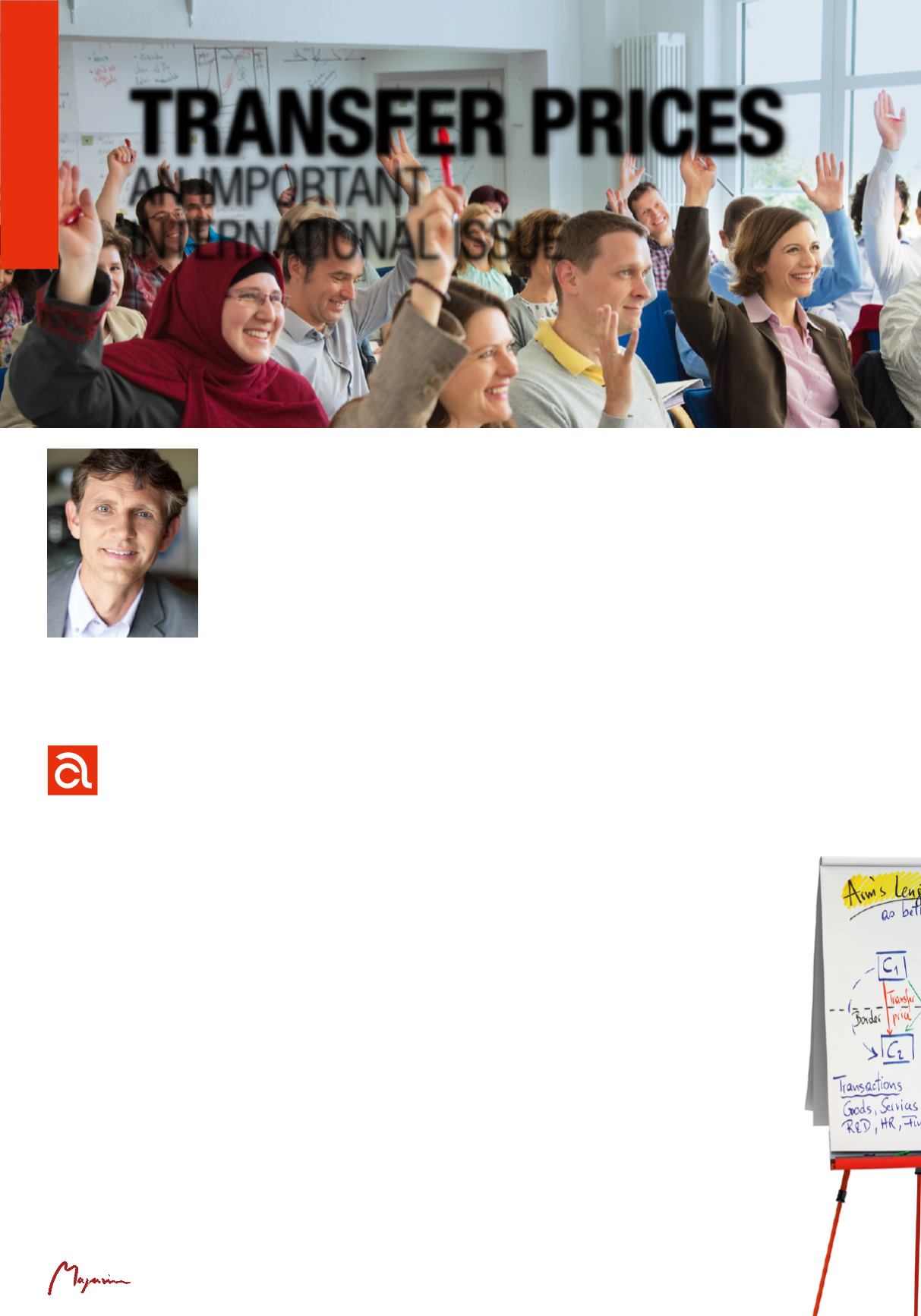

In order to achieve fairness in taxation between countries,

the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and

Development) states that transfer prices must meet certain

requirements, including a comparison with third parties. This

approach, also called the arm’s length principle, is described

by the OECD in its Transfer Pricing Guidelines as follows:

“

The arm’s length principle requires that com-

pensation for any intercompany transaction shall

conform to the level that would have applied had

the transaction taken place between unrelated

(third) parties under similar conditions.

”

If so-called “related companies” conduct business with each

other across national borders, they must observe these

fiscal rules. Permanent establishments (place of business)

are a particularly important problem in this regard. While

controllers are informed about operational projects and

the activities of employees in foreign countries, they are

often unfamiliar with the tax rules governing these new

places of business and “permanent” establishments. On the

other hand, the tax department is easily able to determine

TAX LAW VERSUS PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT?

One of the focal points in our 5-level diploma programme is

performance measurement. In discussions with our clients we have

found that tax-based transfer prices in international corporations dilute

transparency about the company’s actual performance. Indeed, in

some cases management metrics still in use today are even made

completely obsolete. This is a new challenge for us controllers.

whether a permanent establishment exists under domestic

(or foreign) law, but it is too far removed from the operational

business to become aware of the events that might lead

to a permanent establishment. According tax authorities a

permanent establishment is quite often founded based on

the number of days that an employee spends abroad. The

limit in many countries is 183 days. If an employee is au-

thorised by the company to conclude business agreements

– often called signature authority – this, too, usually leads

to the foundation of a permanent establish-

ment. In such cases it is generally irrelevant

whether this authorisation is based on legal

or commercial rules. Tax law focuses on

an activity’s economic substance, which

has individual phases (negotiations about

the type and scope of the performance,

pricing, payment and delivery conditions,

contract signature, etc.) within the overall

process until an agreement is concluded.

Legal tricks to circumvent this signature

authority are thus fundamentally invalid

from a tax perspective.

Furthermore, we convey to our seminar

participants that, in contrast to what the

title “Transfer Prices” suggests, it is

not just the prices that are relevant,

rather all commercial conditions as-

sociated with a transaction, such